This post explains Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE). RoPE is now widely used in modern LLMs including LLaMA, PaLM, and others. The note has been polished by AI based on the original learning notes of the author.

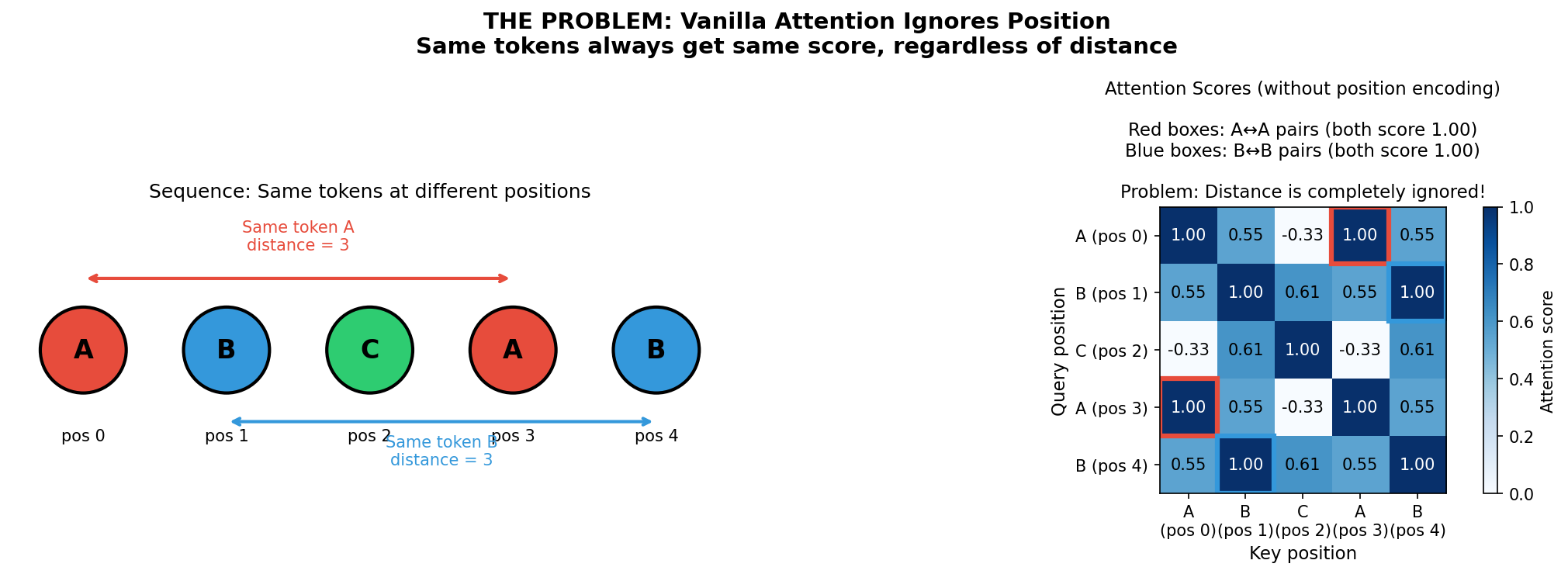

The Problem: Vanilla Attention Ignores Position

In the transformer attention mechanism, each token produces three vectors: a query (representing “what am I looking for?”), a key (representing “what do I contain?”), and a value (the actual content to retrieve). The attention score between two tokens is computed as the dot product of the query and key:

$$\text{score} = q \cdot k$$Consider this dot product in isolation. If we ignore everything else, the score depends only on the content of the two tokens — not on where they appear in the sequence. The same pair of tokens produces the same score whether they are adjacent or 100 tokens apart.1

RoPE offers an elegant alternative: instead of adding position information to the embeddings, it encodes relative position directly into the attention score computation.

The Core Idea: “Twist” the Dot Product by Distance

The idea behind RoPE is essentially asking: can we “twist” how we compare two vectors based on how far apart they are?

Instead of a single dot product, can we create a “distance-2 dot product” when two tokens are two positions apart, a “distance-3 dot product” when three apart, and so on? If we can do this, the positional information will be reflected in the computed attention weight, and the model can learn to use this information during training.

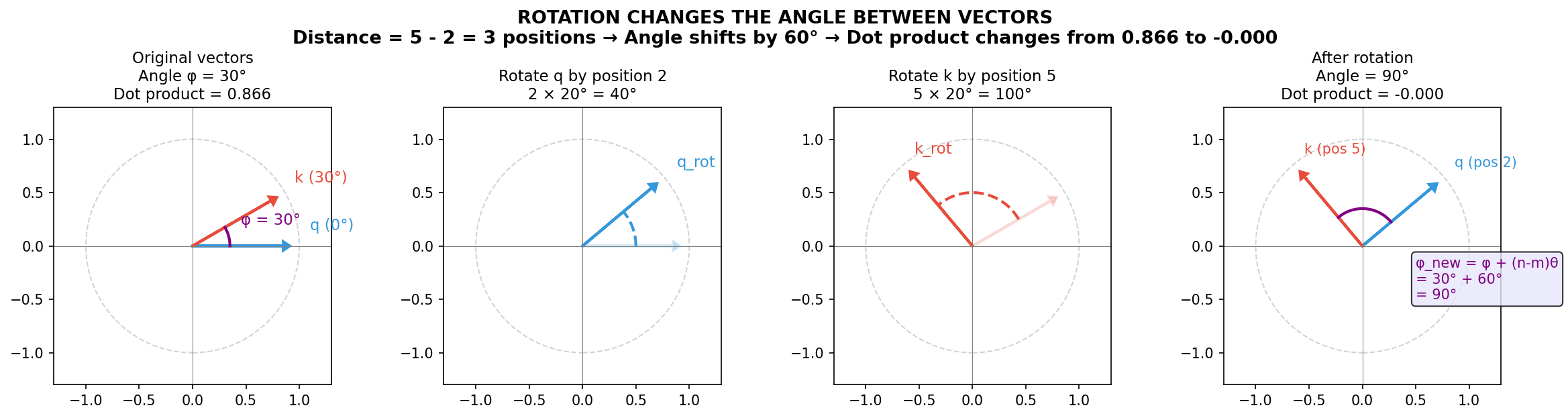

The Solution: Rotate Vectors by Their Position

To build intuition, let’s use $\vec{a}$ and $\vec{b}$ to represent a generic query-key pair. Recall that the dot product of two vectors is:

$$\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b} = \|\vec{a}\|\|\vec{b}\|\cos\phi$$where $\phi$ is the angle between the two vectors.

RoPE’s clever trick is to rotate each vector according to its position before computing the dot product. If we rotate $\vec{a}$ (at position $m$) by angle $m\theta$ and rotate $\vec{b}$ (at position $n$) by angle $n\theta$, then the angle between the rotated vectors changes.

Here’s why: when both vectors rotate counterclockwise (the same direction), the angle between them shifts by the difference in their rotation amounts. If $\vec{a}$ rotates by $m\theta$ and $\vec{b}$ rotates by $n\theta$, the new angle becomes:

$$\phi_{\text{new}} = \phi + (n - m)\theta$$The resulting dot product is:

$$\vec{a}_{\text{rot}} \cdot \vec{b}_{\text{rot}} = \|\vec{a}\|\|\vec{b}\|\cos\big(\phi + (n-m)\theta\big)$$Now the dot product depends on the relative distance $(n - m)$, not the absolute positions. Different distances produce different scores, giving the transformer a way to distinguish them.

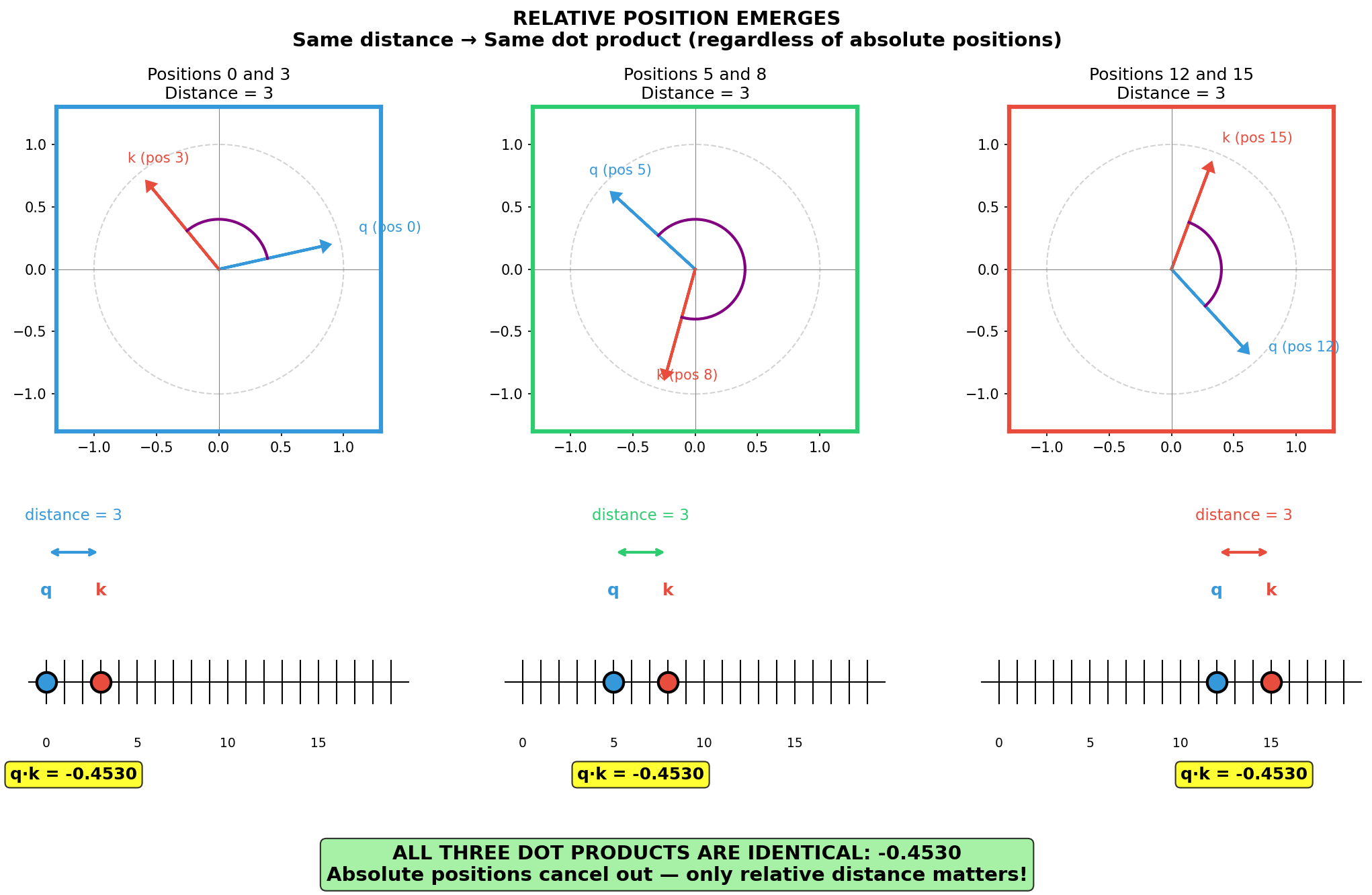

Why Relative Position Emerges

This deserves emphasis. If query $q$ is at position $m$ and key $k$ is at position $n$:

$$q_m = R(m\theta) \cdot q, \quad k_n = R(n\theta) \cdot k$$where $R(\alpha)$ denotes a rotation matrix by angle $\alpha$. The dot product becomes:

$$q_m^T k_n = q^T R(-m\theta) R(n\theta) k = q^T R\big((n-m)\theta\big) k$$Here we used the fact that $R(m\theta)^T = R(-m\theta)$ — the transpose of a rotation matrix is its inverse (rotating backwards). Since rotation matrices compose by adding angles, $R(-m\theta) R(n\theta) = R((n-m)\theta)$.

The absolute positions $m$ and $n$ cancel out, leaving only the difference $(n - m)$. This is the mathematical heart of RoPE.

Important: RoPE is applied only to queries and keys, not to values. The values pass through unchanged — only the attention scores are position-modulated, not the content being retrieved.

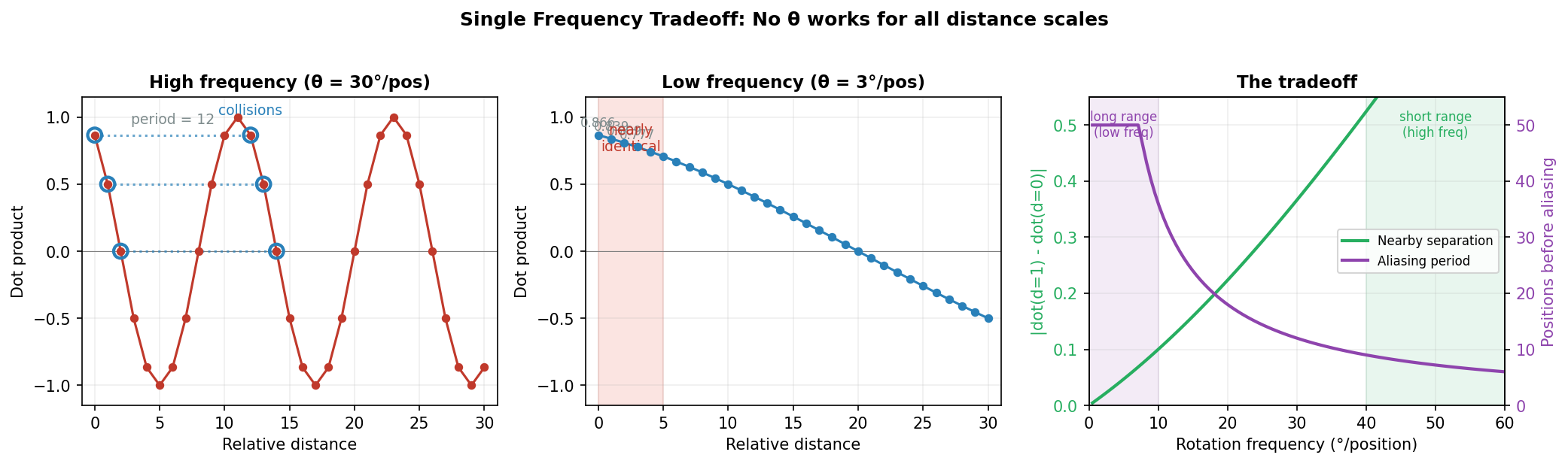

The Aliasing Problem: Single Frequency Fails

The naive implementation has a critical limitation: the cosine function is periodic.

To illustrate, let’s use degrees (we’ll switch to radians later for the actual implementation). Say we choose $\theta = 30°$ per position. Then:

| Distance | Rotation Difference | Cosine Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30° | 0.866 |

| 13 | 390° = 30° | 0.866 |

Distance 1 and distance 13 produce identical scores — they become indistinguishable. This is an aliasing problem.

One idea might be to make $\theta$ very small, say $1°$, so the period becomes 360 positions. But that creates a different problem:

| Distance | Rotation Difference | Cosine Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1° | 0.99985 |

| 2 | 2° | 0.99939 |

Now distance-1 and distance-2 pairs are almost indistinguishable — the signal is too weak.

We face a dilemma:

- High frequency (large θ): Nearby positions are distinct, but distant positions collide

- Low frequency (small θ): Distant positions are distinct, but nearby positions blur together

No single frequency works for all distance scales.

The Multi-Frequency Solution

To solve this, RoPE rotates different segments of the vector at different rates.

Before jumping to the full implementation, let’s see why multiple frequencies help using a simple example where we break the vector into two segments.

A dot product of high-dimensional vectors can be decomposed into parts. Denote the lower half of $\vec{a}$ as $\vec{a_l}$ and the upper half as $\vec{a_u}$:

$$ \vec{a} \cdot \vec{b} = \vec{a_l} \cdot \vec{b_l} + \vec{a_u} \cdot \vec{b_u} = \|a_l\|\|b_l\|\cos\phi_1 + \|a_u\|\|b_u\|\cos\phi_2 $$where $\phi_1$ is the angle between $\vec{a_l}$ and $\vec{b_l}$, and $\phi_2$ is the angle between $\vec{a_u}$ and $\vec{b_u}$.

Now, if we rotate the two segments at different rates — say the lower half at $\theta_1$ per position and the upper half at $\theta_2$ per position — we get:

$$ \vec{a}_{\text{rot}} \cdot \vec{b}_{\text{rot}} = \|a_l\|\|b_l\|\cos(\phi_1 + \theta_1 \times \Delta) + \|a_u\|\|b_u\|\cos(\phi_2 + \theta_2 \times \Delta) $$where $\Delta = n - m$ is the relative distance.

This is a sum of two cosines at different frequencies. Even if one frequency causes a collision (e.g., $\theta_1 \times \Delta$ wraps around to the same angle), the other frequency likely won’t. The two terms together create a more unique signature for each distance.

Partitioning into Pairs

In practice, RoPE extends this idea further: instead of two halves, we partition the vector into consecutive pairs of dimensions, and each pair rotates at its own frequency. This gives us $d/2$ different frequencies, making collisions virtually impossible. Each pair is treated as an independent 2D vector:

$$\vec{a} = \underbrace{[a_0, a_1]}_{\text{Pair 0}}, \underbrace{[a_2, a_3]}_{\text{Pair 1}}, \ldots, \underbrace{[a_{d-2}, a_{d-1}]}_{\text{Pair } d/2-1}$$Why pairs of 2? Because 2D is the minimum dimension where rotation is meaningful. A 1D “rotation” would just be a sign flip, which cannot encode continuous position information.

Different Frequencies per Pair

Each pair $j$ is assigned its own rotation frequency (now in radians, as used in actual implementations):

$$\theta_j = 10000^{-2j/d}$$This creates a geometric progression. The wavelength (positions per full $2\pi$ rotation) is $2\pi / \theta_j$:

| Pair | Frequency (rad/pos) | Wavelength (positions per full rotation) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (first) | $\theta_0 = 1$ | $2\pi \approx 6$ positions |

| 1 | $\theta_1 \approx 0.1$ | ~63 positions |

| … | … | … |

| $d/2-1$ (last) | $\theta_{d/2-1} \approx 0.0001$ | ~63,000 positions |

Early pairs (low index) rotate fast — they’re sensitive to nearby positions but alias quickly.

Later pairs (high index) rotate slowly — they distinguish distant positions but blur nearby ones.

Together, they cover all distance scales without tradeoffs.

The Clock Analogy

This is exactly how a clock encodes time:

- Second hand (high frequency): Distinguishes moments within a minute, but 1:00:30 and 1:01:30 have the same second hand position

- Minute hand (medium frequency): Distinguishes times within an hour

- Hour hand (low frequency): Distinguishes times across the day

No single hand can uniquely identify all times, but together they form an unambiguous representation.

Computing the Rotated Vector

At position $m$, each pair rotates by its own angle:

$$\text{Pair } j \text{ rotates by } m \times \theta_j$$The rotation is applied independently to each pair:

$$\begin{pmatrix} a'_{2j} \\ a'_{2j+1} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \cos(m\theta_j) & -\sin(m\theta_j) \\ \sin(m\theta_j) & \cos(m\theta_j) \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} a_{2j} \\ a_{2j+1} \end{pmatrix}$$The full transformation is a block-diagonal rotation matrix:

$$R_m = \begin{pmatrix} R(m\theta_0) & & & \\ & R(m\theta_1) & & \\ & & \ddots & \\ & & & R(m\theta_{d/2-1}) \end{pmatrix}$$The Final Dot Product

When we compute the dot product of two rotated vectors, each pair contributes independently. Let $\vec{q}_j$ and $\vec{k}_j$ denote the $j$-th 2D pair of the query and key vectors:

$$q'_m \cdot k'_n = \sum_{j=0}^{d/2-1} \Big[ \|\vec{q}_j\|\|\vec{k}_j\|\cos\big(\phi_j + (n-m)\theta_j\big) \Big]$$where $\phi_j$ is the original angle between $\vec{q}_j$ and $\vec{k}_j$.

This is a sum of cosines at different frequencies — analogous to a Fourier series. The combination of many frequencies creates a unique “fingerprint” for each relative distance, solving the aliasing problem completely.

Summary

| Concept | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Problem | Vanilla attention ignores token positions |

| Solution | Rotate query/key vectors by their position before dot product |

| Why it works | Rotation changes the angle between vectors; the change depends only on relative position |

| Aliasing problem | A single rotation frequency causes distant positions to collide |

| Multi-frequency fix | Different dimension pairs rotate at different speeds, covering all distance scales |

| Frequency formula | $\theta_j = 10000^{-2j/d}$ (radians), giving fast rotation for early pairs, slow for later pairs |

| Applied to | Queries and keys only (not values) |

The elegance of RoPE lies in encoding relative position through rotation — a geometric operation that naturally produces position-dependent similarity without adding any learnable parameters. The model learns to use this position information through its existing $W_Q$ and $W_K$ projection matrices.

The original GPT-2 doesn’t ignore position entirely — it uses learned absolute positional embeddings added to token embeddings before computing Q, K, and V. However, this approach has limitations: the model must learn separate embeddings for each absolute position, and it struggles to generalize to sequence lengths not seen during training. ↩︎